Fri 31 Mar 2017

A Transformative Parenting Mediation Model

Posted by Heverton.Oliveira

Parenting mediation can be uplifting and affirming.

The key is using a model that works for the parents and provides a parenting model that starts with a truce, then works towards mid and long term parenting goals. During the past 30 years I have developed a model that has been embraced by most of the parents I have worked with. This paper explains the model while linking it to conflict resolution and conflict transformation theory.

One of the texts in my first Family Mediation course was Isolina Ricci’s Mom’s House Dad’s House. In brief, the book encourages a post-separation model of childrearing where the children perceive that they reside in two homes, Mom’s and Dad’s. Over the decades, I developed a model so people could apply Mom’s House Dad’s House in their own situation. They have used the model through an endless variation of options. Some lived hundreds or thousands of kilometres from each other. Some had determined that they now had a different sexual orientation. Some had a sophisticated parenting outlook while some had a very simple approach. While there have been failures, times when some families have been screened out, and a good number of cases where parents have chosen not to adopt the model, overall the reaction has been very positive. Feedback from parents confirms that it can have a lasting impact.

Introduction to the Model

When people inquire about parenting mediation, I present two main themes to introduce Mom’s House Dad’s House. The first theme is, “I wonder if what you want is a way in which the dysfunction between the two of you does not pass to your children”. This frame immediately captures the triangulated nature of their dispute, and offers a way out of the triangle.

The theory behind this theme of dysfunction is that there is a triangle with points made up of parent, parent and child. This triangle equals dysfunction, and ending the triangulation ends the dysfunction.

The second theme is aimed more at those people who have a working arrangement that needs to be confirmed. “Are you interested in a model where you have more than a truce, a model in which your children can thrive?” The assumption is that whatever peace the parents have developed can be expanded beyond the short or even the medium term to a new and improved long term family structure and dynamic.

The idea of using a three level concept of truce, mid-term and long term settlement comes from John Paul Lederach’s idea of “peacemaker, peacekeeper and peacebuilder”. Peacemaking means setting aside hostilities while discussions take place. Peacekeeping addresses mid term problems like scheduling, safety, basic communication. Peacebuilding invites parties to embrace a new structure/process focused around the child thriving.

Both themes motivate parents away from their instinctual need to either avoid or fight the other towards a common goal of a mutually shared better outcome for the children. The model works when each parent believes it will also provide a better outcome for that parent.

Step 1: Introduce Children, Their Present and Their Future

At most mediations, parties will have worked out some kind of financial arrangement before we get to the parenting issues. This is sometimes problematic as they may have the idea from their financial negotiations that mediation involves negotiation or compromise. However, if the parties cannot grasp that financial issues may have integrative elements, the mediator has a caution about how ambitious to be with the parenting model. The key is to reach the greatest depth available, and for some people, the greatest depth is some insight into what guardianship while separated means, a schedule, some safety rules with consequences, and some simple communication tools and expectations.

While the first part of our Mom’s House Dad’s House model deals with basic behaviours, the last steps are counter- intuitive. This raises a challenge for mediators for parents who have difficulty in using a cognitive model for change. The more parents find answers that integrate with the other (as opposed to distribution of rights or time or power), the deeper their resolution can be. By mediating finances first, a mediator can get a good idea about how far parents can be encouraged to deepen their ideas. All parents benefit from having a truce. Thereafter, the greater the integration, the better the chances of good outcomes for the children. (This focus on maximizing integration and reducing distribution is found in Bernie Mayer’s The Dynamics of Conflict Resolution).

Picture

Starting the parenting model: First someone provides a picture of the children. As the parents compete to show a picture, or only one has a picture on their phone, or the chosen picture shows that parent in a superior light, the mediator gets more information about the dynamics. Most of the time, the parents are proud to show the picture around the circle.

Starting the parenting model: First someone provides a picture of the children. As the parents compete to show a picture, or only one has a picture on their phone, or the chosen picture shows that parent in a superior light, the mediator gets more information about the dynamics. Most of the time, the parents are proud to show the picture around the circle.

One Paragraph

Then each parent is given a chance for a one paragraph description of each child. I take careful notes. It is interesting how often these descriptors help explain the family’s challenges. There may be health or social concerns. There will always be wonderful adjectives. Many of the descriptors show how the child reacts to others including siblings or parents or friends. When these are concerns for the parents (or should be concerns), those are important facts to use when explaining the advantages of the parents working together.

Age 22

Next is to inquire what each parent hopes for and then what each parent is afraid of, when the child reaches adulthood. I use age 22 as I can briefly relate how I was relatively successful and independent at that age. In contrast, I have met 22 year olds with drug or alcohol problems, or who dropped out or who are receiving psychiatric treatment or have already had many children. The parents will list a number of items and often will agree with each other (although often there are material differences). I analyze these out loud because if the parents hope for stability, good relations with each parent etc. and are afraid of alienation, I take their comments as very good indicators that their fears are driven by their relational dysfunction. I usually suggest that this may be the case and that if they were not in their present situation, they would be more ambitious for the child. Most are somewhat ambitious although many want the child to have the freedom to find their own way. This is an important theme that will come up throughout the mediation. My encouragement is for the parents to be role models rather than assuming that the children bear the burden of figuring it all out for themselves. Many people I that I meet at the mediation table, though, did not have strong role models.

Purpose of Step 1

The focus on the child is important. This starts the mediation with the child instead of the parent. The focus is about the picture, the children as they are at present, and their hopes and fears for the future. The next stages of the mediation will be totally child-centric, and this sets the tone.

Unlike conflict resolution, conflict transformation is not simply ending something destructive, but also building something that is desired. The horizon for change is mid to long term. It promotes a response to symptoms and at the same time engagement in the systems in which the conflict is embedded. JP Lederach, The Little Book of Conflict Transformation p. 33.

More importantly, the long-term future target is the real goal for the mediation. It is not about who gets next weekend and what happens at Christmas. It is how the child has a successful outcome and how the parents view success and failure. Interestingly most parents have not articulated their long-term goals with the other much less developed a strategy to get there.

Step 2: How Children Fail

The most useful image of most parents’ fears is that their children will “fall through the cracks”. This very useful metaphor captures the idea of a path to the future, perhaps made of wooden slats, and that walking on such a sidewalk has serious risks. There is no paved road to success. Instead children are at risk of falling through instead of moving ahead.

Step 2 acknowledges this, and deliberately develops a model of failure. From a theoretical point of view, the triangulation of the child and parents is the problem being addressed. It is addressed though exploring how children grow and more specifically how their brains develop. This idea of how the brain develops is taken from the work of Bill Eddy.

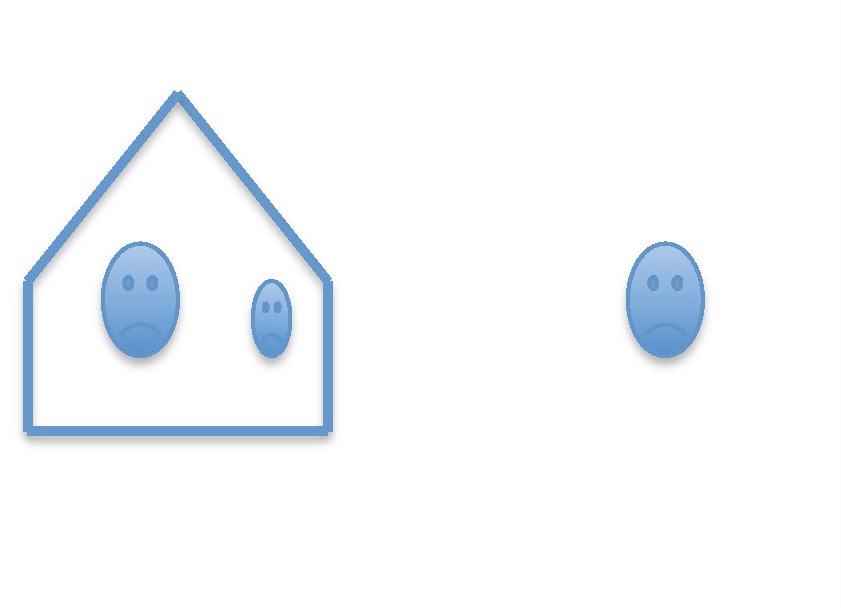

Picture of House and Man in Field

I draw a stick figure family (mom and kids) in a house with dad on the outside alone. I make sure that these are similar to their family, but make the children a slightly different age, as these children are about to fail. Once the parents catch on that this is a picture of a separated family, I ask them to describe the reaction of the child to learning that the parents are separated. This leads to a discussion of how a separation looks through the eyes of a child.

I draw a stick figure family (mom and kids) in a house with dad on the outside alone. I make sure that these are similar to their family, but make the children a slightly different age, as these children are about to fail. Once the parents catch on that this is a picture of a separated family, I ask them to describe the reaction of the child to learning that the parents are separated. This leads to a discussion of how a separation looks through the eyes of a child.

The purpose of the model is to allow the parents to explore how children are part of the separation process. With a little leading, parents accept that children consider that the separation is not normal (the predictable patterns are changed); that they consider it wrong; that they consider that they are responsible in some way; and that they need to fix things. Then the child works at getting things back the way they were. This might start by asking mom about dad, or talking to dad about mom, and being very nice, or otherwise behaving in ways to encourage the parents to engage.

Over time, as the parents figure out how to discourage the children from forcing them to talk about the other, the children’s instincts lead them to focus on those aspects of mom that dad is interested in (money?) and those aspects of dad that mom is interested in (new friends?). They learn to push buttons, get attention, and keep the parents engaged. This often leads to exaggerating and lying.

Parents seem to have little problem in helping develop this model and in understanding that the dynamic is flawed. They often give examples from their lives about how the children are triangulating them, by talking to mom about problems that dad is having, or telling dad stories about mom and so on. The parents can see that this is not how they want their separation to work.

At this point I go through how a child’s brain develops, taken from a Bill Eddy lecture that I attended. Eddy suggested three stages, and unless the first two are handled appropriately, high risks are present for the third.

Age 1-4 a child operates from the right side of the brain, which is the more creative, but also the more insecure side of the brain. The brain is learning in “schemas” (these are “sheets” of information instead of individual facts). The child is looking for security and reliability, in the “nest”. By the time the child reaches 5 years, if that child does not have a reasonably stable and adjusted approach, there can be major challenges in the future with varying challenges of insecurity, anxiety or confidence, as this side of the brain is no longer dominant.

Age 5-11 a child is now in the left side, which is the organizing and patterning side. The child is able to take instructions now from a non-parent and work with non-siblings which is why, world wide, this is the age to start school. The child is starting on the road to independence, and is also learning to apply the brain in more sophisticated ways (from words to sentences to paragraphs to creative concepts, or from adding to multiplying to geometry to trig to calculus and so on through languages, sciences, social sciences etc.).

Age 12+ a child’s prefrontal cortex (the non-instinctual part of the brain) takes on less of a role as hormones and other stimuli dominate the brain. The child is swamped with many new thoughts and uncertainties. This includes sex, education, motivation, and so on. The child considers him or herself to be much more independent and acts accordingly. This is not automatically rejection of the family. For example, the child may still recognize there is a curfew, but not take it into account until it is already 10:30 pm and she still needs 30 minutes to get home.

In terms of our model, it is easy for the parents to see that in the puberty stage, the child from our dysfunction model considers him or herself to be the adult in the relationship. There is no respect for a parent who is seen as dysfunctional, and therefore perhaps weak and inadequate or a bully and uncaring. As the adult, the child makes the big decisions, such as whether to attend school, or try in school. When deciding on a question such as whether to try smoking or drinking or drugs, they will gravitate to those peers who have access and experience. Since they have been manipulating the parents since the separation, they are not willing to accept that parent as either an adult with authority over them or as a peer whose views they might consider. They consider themselves independent!

The lessons here are:

- Parents are often trying to end the dysfunction between them, by separating, and the children keep the dysfunction going. The children make the triangulation continue. They drive the dysfunction bus.

- When parents do not work as a team, the children can and will play them against each other, perhaps to encourage reconciliation at first, but over time for attention and in reaction to the way the parent is dealing with the separation.

- The result is a loss of respect by the child of the parent or both parents. This will be devastating in the teen years as described below.

- Each parent is often genuinely making an effort of showing the child that they love and care for them. However the result of their “common sense” approach to the dysfunction is more dysfunction. It is often the structure that is at fault, not the individual parents.

- When the children fall through the cracks in the puberty years, it is because they have not seen themselves as “children” during the separated period but have been part of the triangle between themselves and each parent. Sometimes as described, this leads to them making crucial unhealthy decisions in their teen years relating to education, sex, drugs or other challenges. In other cases, where a parent demonstrates need or insecurity to the child, they may take on the role of replacement spouse. Either way, they have taken on a “leader” role. They have not been allowed to be “children”.

- The first goal of mediation is ending this dysfunction so that the parent can keep the role of adult and the children can grow up as “children”.

Step 3: Making a Truce

Here I ask the parents to fix the picture. Parents have added a number of things to the picture: they might add one parent into the home of the other, attach another house to the house, draw an X through the father, put those in the house (mom, kids) outside with dad, with hearts, draw a heart around the whole thing, draw a house around the whole thing, and so on. All the effort demonstrates an interest in working this out. Even the “X” was useful, as it opened a discussion about what dad’s role and value should be.

Pictures are very useful, as the parents can listen to words, nod, or even make thoughtful comments, but THEN revert back to a different track after the slightest provocation. A picture seems to work at a different level, particularly when they have to help draw it.

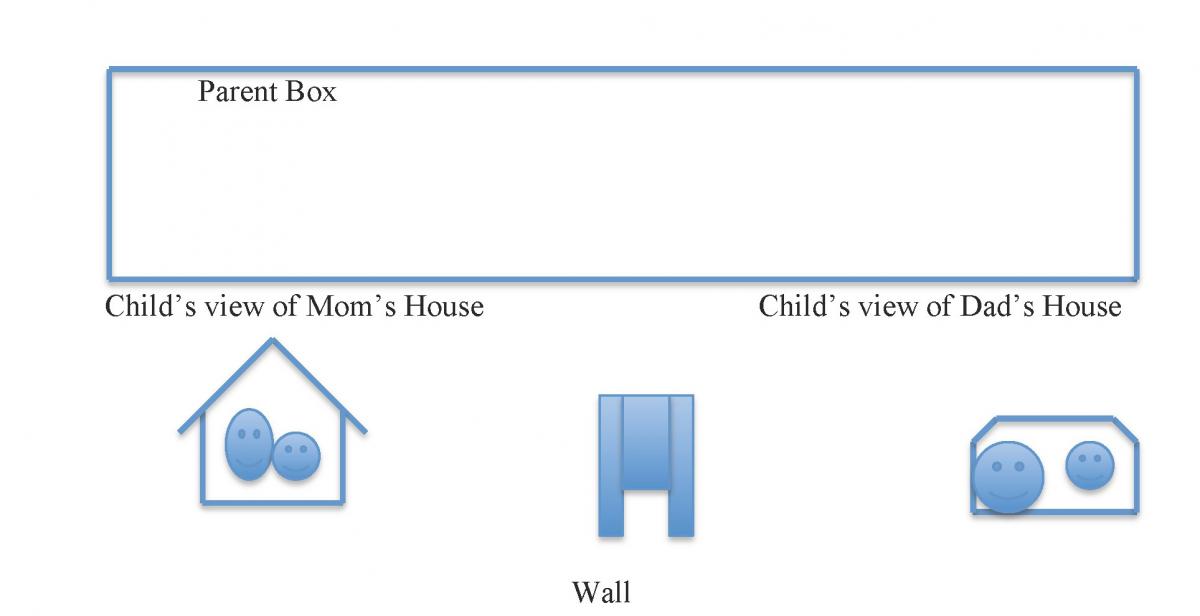

Eventually, the parents or mediator with the encouragement of the parents, draws two houses, a mom’s house and a dad’s house with the children in both houses. When seen through the eyes of a child, the picture illustrates the idea of two separate relationships, one with mom and one with dad. The houses are deliberately made to be different, both in shape and in terms of the landscaping (perhaps a tree in one, a chimney in the other, a cat in one or a quad in the other and so on). If the child saw each house as the same as the other, what need is there for two parents?

The parents are asked for what else the picture needs. They may put in a path between the homes. Or they may put in cell phones so the other parent can be in touch. They are always shocked when the mediator adds a thick wall between the homes, (although relieved slightly when a child-sized door is added).

Understanding the purpose and function of the Wall is not easy. It is often necessary to remind the parents of what evil is the mediation is attempting to address. The answer is: how do we keep the dysfunction of the parents from passing to the children? The Wall is the answer. Only when the children no longer live in a triangulated world can the dysfunction stop.

Also, it is essential for the parents to see that the picture must be seen through a child’s eyes. The child is expected to be free from influence from the other side of the Wall and to stop trying to manipulate things to where the child accepts that the parent on the other side is no longer enmeshed with the parent’s world on this side.

Finally, I stress that this is not intentional behaviour on the part of the child. This starts with their subconscious, and then develops at that level.

If the parent box has not been drawn to this point, it needs to be added, so they can see that there is a major part of the picture dedicated to how the parents work together. It is the children who are to live in two separate worlds, while the parents (who are separated) need to figure out how they work together.

At this point I ask if they like this model. They generally do. If they have feedback, it is usually about items that belong in the parent box.

While the theme of “let the children be children and the adults be adults” will probably have come up several times in the mediation, this is a key focus now. When the children are manipulating parents against each other (or behaving as a replacement spouse) that child has the role of adult. More importantly, it is not whether the parent sees it or not that matters, it is the perception of the child that is crucial.

For that reason, I set this scene and ask this question: imagine that it is your turn to deliver the child(ren) to (other parent). As she (they) gets out of the pickup, you have a chance to say those last few words before they go up the sidewalk to the door. What do you say? After I get the answer, I ask the other. I make notes of what is said.

Answers include: I love you, I’ll call you, be nice for Dad, do your homework, remember your medication, I’ll see you in 3 days, and so on. After I get these answers, I ask what they think they should say now that they have embraced the Mom’s House Dad’s House model. They are flummoxed. So it is necessary to ask what message they think they should send if they want the children to embrace the model. With some help, they can see that what they want is for the child to know that they are still loved, and encourage the child in the other place, but what the child probably senses is that they are not letting go, that they are setting the rules or tone for what happens at the other end of the sidewalk. Depending on the level of dysfunction, the child may even sense that the parent wants their spirit of love and support to be with them as they face the challenges of being on the other side.

Friedman’s Generation to Generation explains homeostasis and differentiation. Family structure focuses around maintaining balance (homeostasis) while healthy individuals also have a sense of their separate identity (differentiation). Within the structure, therefore, instead of labeling a “challenging” child (or spouse) as a problem, Friedman describes them as “identified patient”. Within the family structure, this person is normally the “squeaky wheel” and therefore gets “grease” (attention). Instead of catering to the squeaking with attention, Friedman’s model encourages others (in our case the parents) to lead in the direction they consider appropriate. This leadership is presented as a non-anxious presence while the leader sets out in the new direction. When the patient (in our case, the child) see one or both parents going in an unexpected direction, the child will react, and try pulling the parent back into the old balance. The relationship will deteriorate. Friedman anticipates three cycles of testing, but after the third, the patient (child) adjusts, and the relationship actually becomes stronger than before the new direction was taken.

I stress to the parents that I am exaggerating to make the point, and tell them that the point is an essential one. It is that if the Mom’s House Dad’s House model is to work, the child has to believe that the parent has bought into the plan. In order to convince the child, the parent has to demonstrate in word and deed that the other parent is absolutely trusted by this parent. Instead of “Remember I love you”, the correct statement is “Remember (other parent) loves you.”

The views of the child are essential to family transition and to ongoing decisions made concerning the child. This is the British Columbia law as set out in the Family Law Act. Our model starts with parents describing their children, thereby putting their actual natures on the table. As the mediation unfolds, the model is designed so that the views of the child can flourish in their separate relationship with each parent. While each separation has certain common themes, each is also unique, particularly when it comes to the challenges and opportunities presented by each child. That must be respected.

At the same time, the heart of the model is that the parents are adults and children are not adults and therefore they must be discouraged from taking on the mantle of adulthood, such as choosing between parents. The heart of Mom’s House Dad’s House is that during the key “falling through the crack years”, if the children have the idea that they are adults, the parents will lose their influence. If the children are free to be children instead of carrying the authority of adulthood, they are likely to turn to their parents when confronted by the dilemmas of those challenging years.

In their teen years, even as children develop more independence and character, this model still strongly discourages the idea that children can be the main decision-makers respecting “adult decisions”. Children flourish when they can have appropriate and stimulating relationships with each parent and siblings. While this varies with facts and age, the key is that children have the best chance when there is an appropriate relationship with each parent. Safety is primary. It is also a key driver of triangulation, as one parent either oversees the other, or expects the child to do so. Where safety is an issue, this model invites parents to find a trustworthy third party as the overseer and as child confidante.

Obviously, this is counter-intuitive to an extreme. The parents are separating. They often have serious trust issues. They often have safety issues. They have worries about what is happening on the other side of that Wall. The mediator encourages them to put all of those topics into the parent box. When either parent either intentionally or subconsciously suggest that any of these issues is the responsibility of the child, the dysfunction has again taken over. However when the child perceives that each parent does trust the other then the triangulation has been broken. I explain that the children will test the parents. If they did not, they would not be the bright and engaging children that I was introduced to.

And I explain the corollary, that when the child is convinced that the parents trust each other, the way the parents talk about their own love for the child or their expectations about behaviour or other topics is not nearly as important. It is the perception of the child that matters. Once the child perceives that he or she lives in a Mom’s House Dad’s House world, the dysfunction based on the separation should cease.

At this point we move into the Parent’s Box and look at topics like communication, trust building, safety, scheduling, rules of guardianship, step parents, and so on. In particular, I encourage the parents to develop a communication model by which they share key information about their life with the child (which should be in areas of health, spiritual development, education and social activities). From the obvious perspective, when the parent already knows a bit about an episode it will be difficult for the child to confabulate about it. Much more importantly, when a parent knows of something good (“what’s this I hear about you going fishing with your mom and catching something”), it not only is evidence for the child that this parent loves what is happening at the other residence, but also provides a healthy entry point for the parent to have a comfortable non- threatening or agenda-driven conversation with a child. When reciprocated, the results are well-adjusted children. And when problems arise, there is a history of small talk and ease of conversation that allows the problems to simply be another part of the conversation.

Depending on the level of distrust, I may spend significant time allowing the parents to develop models of little steps, of enforced small talk (non-agenda driven conversations or communications). If safety is an issue, I raise topics such as how a child can be safe without one parent being the child’s social worker, or the police officer over the other parent. There may be negotiations about consequences for breaking commitments, and so on. The idea is to create a Parent’s Box that allows the child to be a child no matter what is happening with the adults, and that allows the adults a structure and process for addressing the various issues that they will face as the children grow and the parents’ situations change and both problems and improvements happen.

When all of this is accomplished (and the range and variety of the discussions confirms just how complicated and interesting humans are), I compliment the parents on having achieved a truce.

The Plenert School of Cooking

The next step is a model in which the children will thrive. I use three stories, which start with the Plenert School of Cooking. Each mediator will have their own stories, and this one has worked very well in my mediations. For children to thrive, they need to see their parents as differentiated and they need to see themselves as differentiated as well. Triangulation is an attempt to pull everything back into the balance. Having found a model by which triangulation ceases, the goal now is for the child to make the most of the relationship with each parent. As well, these goals must be tied to the long term goals that the parents set at the beginning of the mediation, when they outlined their ambitions (hopes) and deepest concerns (fears) for when the child left home.

The next step is a model in which the children will thrive. I use three stories, which start with the Plenert School of Cooking. Each mediator will have their own stories, and this one has worked very well in my mediations. For children to thrive, they need to see their parents as differentiated and they need to see themselves as differentiated as well. Triangulation is an attempt to pull everything back into the balance. Having found a model by which triangulation ceases, the goal now is for the child to make the most of the relationship with each parent. As well, these goals must be tied to the long term goals that the parents set at the beginning of the mediation, when they outlined their ambitions (hopes) and deepest concerns (fears) for when the child left home.

Very simply, the Plenert School of Cooking is the label my wife, Delores, put on the training she gave our girls starting when they were 5 and 8. In that first summer, they learned to bake muffins once a week. Each year, the children took on more advanced tasks. In Junior High, they were sewing their own clothes. By the time they were in grade 11, the Plenert School included menu planning, budgeting, shopping, and growing vegetables.

In mediations, I mention “the Plenert Schools of Cooking, Baking, Sewing and Gardening”. I then explain how one daughter made a beautiful silk wedding dress, and the other made her own suit jackets for her summer jobs while at university. I ask: “Did they catch onto what was important to their mother?” The answer is always “Yes”. Then I say: “What if, in that first year, I had said “Boston Pizza cooks” (based on ads in which Boston Pizza ridicules the idea of people making their own meals). This leads to a discussion on how easy it is to undermine everything one parent is trying to do, and also on how a parent may simply think they are being funny but the damage can be huge. Their child will only get the best out of one parent when not undermined by the other.

I then talk about how in the summers we would go to a classical concert, a museum and walk through a university campus. I grew up in the city, and in this way my children were introduced to cities. As a result, when they were in Grade XII, the question was never if they would go to university, it was a matter of which major they would pick. In this way, I show how the strengths of each parent and the key identity emphases of each parent open the door to mid and long term growth for the children.

In order for the child to really thrive, though, the child’s identity needs to be enhanced. Differentiation means that the child must see him or herself as special, and in fact, the child should be encouraged to develop independence. This is true transformation. In this regard, Delores encouraged and supported each child as they developed a skill in an area outside of either of our expertise. One daughter rode horses, the other joined ballet.

The result was children who got the best out of each parent and also had the confidence to be different on their own. Delores and I would have listed these values - home economics; university; and special hobbies – high in our hopes for our children. We would have added strong relationships as well as an understanding of our background and faith as Mennonite Christians.

This ties closely to the more expansive subsections of s. 41 of the Family Law Act where the legislation mentions parental responsibilities, in particular areas of health, education, extracurricular activities, cultural, linguistic, religious and spiritual upbringing and heritage.

I sometimes do the Plenert School stories before we deal with the Parenting Box. The test is how much dysfunction the parents demonstrate. Those who are able to work cognitively enjoy the Plenert School and it drives their desire to make their model as viable as possible. Those who are more confrontational need the opportunity of addressing their concerns and distrust. While I have other models for working with their dynamics, if they feel that this is a lecture rather than their advancing their issues, they will get nothing from the stories.

We always end back in the Parenting Box, and work on as many or as few details as the parents require. The Separation Agreement will include guardianship, parenting, and child support including special and extraordinary expenses. Other topics may be incorporated in the Separation Agreement or not, depending on what is appropriate and the instructions of the parents.

Conclusion

In one hour, a mediator can guide a couple through most of the Mom’s House Dad’s House model. And even in parenting mediations where the parents do not invite such a comprehensive exploration, they can still can explore ideas such as: “how does your dysfunction make things worse” and “parents being adults so children can be kids”. Parents blame themselves or the other for the stressors the children exhibit, and do not see how the separation and its aftermath causes the child to drive the dysfunction bus. Parents are desperate for a strong relationship with the child after separation, and do not see how this is perceived through the child’s eyes as a contest between parents. And it is very difficult for most parents to work this out for themselves.

The Mom’s House Dad’s House model offers a healthy structure that honours the identity of each parent. It gives a medium and long-term focus anddirection for the child’s growing up. The image of the Wall offers a quick route to getting a truce. The Parent Box offers a separate process for the key parenting issues, but even more importantly, offers a space in which the parents can stop being “exes” and start being mom and dad, and planning and sharing and cooperating. While this starts with small trust building steps, it leads to a new relationship and connection. With these new patterns, the old patterns and the old labels disappear. This provides motivation, and in particular motivation so that both children and parents thrive instead of simply muddling through.

Wayne Plenert is a retired lawyer and now mediation mentor leading the Northern Navigator project in the Peace River Provincial Courts. He was president of the BC Mediator Roster Society (now Mediate BC) and former chair of Mediate BC's Roster Committee.